By Henk Hadders for Enlivening Edge Magazine

This is part 2 of a 7-part series about the elements of a new social contract for health and sustainability. It proposes new impetus to develop new concepts of health and sustainability, to indicate thresholds for the resources needed for our health and the next generations, and to monitor the actual impacts on these resources. All this serves the idea of maintaining and enhancing the Sustainability of Health by closing health gaps within a geographical place-based health initiative. Part 1 can be found here.

In this article we address the “health gap” looking at the relationship between resources and the goal of “health”, thereby exploring a resource-, asset- or vital-capital based view of health: how efficient are we at achieving this goal given the resources we have (see diagram 1)? There’s something paradoxical about health, as it can be seen both as a means and as a goal, and as an individual and social issue at the same time. It can be seen as part of (individual) human capital or as part of collective social and ecological capital.

We explore “health as a goal” in the context of our place-based initiative in the northern part of The Netherland: Care 4 Sustainable Health (C4SH).

What does a new social contract for a safe and fair operating system for health and sustainability look like, in order to enhance population health given the available health-related vital capital resources in that geographical space?

What is the context and real situation? Are we still in a safe operating space for human health and well-being?

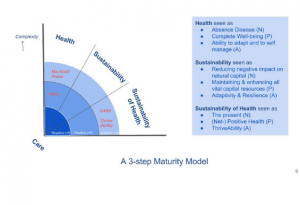

Health, the health care system and the health system are all different concepts, where the healthcare system within the health system is a rather small determinant of health. But what is “health,” what is “sustainability,” and what does “sustainability of health” look like for our future generations? We need to have clear conceptions and definitions to guide us as a bright shining North Star on our journey and as an attractor for our decisions and activities. Using a maturity model, we explore the evolutionary development and define new concepts for health, sustainability and the sustainability of health.

Care 4 Sustainable Health: a place-based health initiative

C4SH is a place-based health initiative focused on a shift from institutions to people and places ( = Northern Netherlands), from service silos to health system outcomes, enabling change from national to local, and closely linked to the notion of geographical health. C4SH is focused on creating New Networks of Health, using the infrastructure of the society Noorden Duurzaam to develop, create and implement a Dutch version of the Nuka System of Care (Alaska). C4SH is also focused on creating a hub and platform for learning, change and transition within these new networks. All this begs for a new regional multi-capital social contract between constituents in Market & Business, State & Government, Commons & Civil Society, and Science. It also begs for an adaptive multi-capital scorecard to measure and report the actual sustainability performance of their activities on the health of all others.

New concepts of Health and Sustainability

What is the C4SH concept of health, sustainability and sustainability of health? We use three steps in our maturity model (Figure 1) to describe the development of these concepts, plotted against the context of increasing complexity: negative, positive and adaptive. These steps are not to be seen as either/or, but as both/and where each step includes and builds on the others as well.

Health

Three definitions can be found around the concept of health and its paradigm shift:

- negative: health seen as absence of disease;

- positive: health seen as a state of complete well-being;

- adaptive: health seen as the ability to adapt and to self-manage, in the face of social, physical, ecological, and emotional challenges.

The conceptions shift from static to dynamic. and from an absolute to a relative perspective.

Health seen as the absence of disease is a rather static and negative definition, and still dominant in mainstream medicine and healthcare.

Language really matters, as doctors don’t take care of our health, but they treat diseases. The World Health Organization defined “health” in a more positive and broader sense in its 1948 constitution as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.

But according to such a definition nearly no one can be deemed truly healthy, so is this definition still realistic? This positive notion of health is also in no way reflected in daily practice, where 95% of activities still remain mainly focused on repair, cure, and prevention of medical diseases and limitations. In The Netherlands, a shift is now taking place towards the introduction, guidance, and use of a more adaptive conception of health, lead by Machteld Huber. She is leading the transition by means of research and new regional pilots.

Adaptivity and resilience is also about a relationship or a dynamic balance between a system and its dynamic environment. Against the background of Complex Adaptive Systems and Complexity Theory, others also look at health as a function of the quality of relationships (Sholom Glouberman (p 35), Zimmerman, Carlson School of Management .)

Sustainability

In the field of sustainability, similar paradigm shifts can be seen (Faber et al), where the hitherto dominant negative and positive conceptions of sustainability are challenged by a radically different approach: adaptivity and resilience. The three conceptions are:

- negative: sustainability seen as removing negative impacts on natural capital;

- positive: sustainability seen as maintaining and enhancing all vital capital resources;

- adaptive: sustainability seen as maintenance or enhancement of adaptivity and resilience.

The Capital Theory Approach is a central part of sustainability science and of methods and tools like: Context Based Sustainability, GRI and Integrated Reporting. Sustainability is about the negative and positive impacts on the stock of vital capital resources needed for our health and well-being.

A new approach in the positive realm is the Net Positive Movement, which not only deals with “doing no harm,” but “doing more good” while investing in the stock of vital capitals.

Sustainability seen as adaptivity and resilience is also about learning, sustainable innovation, and knowledge production. Against the background of Complex Systems Hooker and Brinsmead have explored this third approach in sustainability science in more detail. Space considerations prevent going into more details here. Robinson & Moraes Robinson the authors of “Holonomics” state that “sustainability is about the quality of relationships” and Jyoti Banerjee claims that given its importance, ‘relational capital’ needs to be seen as a separate category, and not “only” as a part of social capital.

Sustainability of Health

To be able to address the issue of sustainable health or the sustainability of health, a first step is using a Capital Theory Approach to describe and redefine health. This leads to a Resource-based view of Health or a Health Asset approach. Aaron Antonovski was the first to develop a positive strength-based approach incorporating resources, while studying the origins of Health (salutogenesis). Morgan and Ziglio (WHO Geneva) promote health and well-being through the asset model, whereby health assets are described as any factor (or resource), which enhances the ability of individuals, communities and populations to maintain and sustain health and well-being.

Asset approaches have been used in many disciplines and at different levels (such as community level Asset Based Community Development , Flora .) In the field of health asset approaches, Scotland and Harry Burns are shining examples (Glasgow .)

Linking an asset approach to health with either positive or adaptive sustainability thinking leads to new combinations and approaches. In the positive realm we mention the US initiative Positive Health and in the adaptive realm we name the ThriveAbility movement. C4SH advocates the Human Flourishing and the ThriveAbility approach in its place-based health initiative, as it combines crucial elements like context-based sustainability, a strong focus on relational capital, learning, knowledge production, and innovation.

The Place, thresholds and allocations

Earth Overshoot Day (Global Footprint Network) comes earlier every year . Global overshoot occurs when humanity’s annual demand of the goods and services that our land and seas can provide, exceeds what Earth’s ecosystems can renew in a year. We already depleted resources beyond their thresholds needed for a just and fair space for humans (see Johan Rockström and the Stockholm Resilience Centre and Kate Raworth and Oxfam). It is clear that new challenges for “health” and “care” will arise, as both face resource limits in this world. We need new impact-performance measurements and metrics that combine micro-performance with macro-challenges in the region regarding “sustainable” health.

Human actors and systems are resource integrators for health and well-being, whether these assets or resources are private, public, or common.

Assets for health are linked to the different ecological and social determinants of health.

But the stock of these health assets needed for a good and safe operating space for human health are being depleted fast by human individuals and collectives. Can we still thrive in the years ahead? Are we crossing thresholds in the carrying capacity of health-related vital capitals? (McElroy )

A threshold is a limit in the carrying capacity of a vital capital, which can either be an upper limit or a lower limit. Water as natural capital is an important determinant for health. A threshold of water in a watershed, for example is an upper limit; a viable wage threshold is a lower limit. Both are thresholds that must be respected if the impact of human systems and organizations on the resources involved (water and wages) are to be sustainable. Thresholds then, are measures of the stocks and flows of vital capitals: measures of their limits or sufficiency that is.

Allocations, by contrast, are fair, just, and proportionate shares of the burdens required to maintain thresholds (in vital capitals) that are assignable to individual actors (e.g., organizations). Once limits in the availability of water resources in a watershed have been determined, for example, allocations of them can be made to individual users. In the case of water, this will typically involve allocations to multiple parties, the sum of which should not exceed the available upper limit (or threshold) of renewable supplies.

We need a regional multi-capital social contract for health and sustainability and new health impact assessment tools to assess measure and report the regional impacts on the carrying capacity of health-related capitals in order to monitor the sustainability of health in the region. If we don’t invest in maintaining the stock of capitals and deplete it instead , the flow will diminish as well.Some years ago I started working on such a true health sustainability scorecard and started to imagine what a “health footprint” for human systems might look like. It’s still work in progress,

References:

(1) In this article we use the words resources, assets, (vital) capitals as synonyms for the same concept.

Henk Hadders is a former Executive Director of the Board of a Mental Health Institute in the Northern part of The Netherlands. After his retirement he started a PhD research about sustainable health, sustainable healthcare and sustainable innovation.

Henk Hadders is a former Executive Director of the Board of a Mental Health Institute in the Northern part of The Netherlands. After his retirement he started a PhD research about sustainable health, sustainable healthcare and sustainable innovation.