By Chris Cowan and originally published at holacracy.org

1. Learn to Love Tension

Tension is not usually a positive term. When we feel tension we try to relieve it, release it, relax. Individuals practicing Holacracy, however, recognize that tensions are powerful. We use the term tension to refer to the feeling you get when you recognize that something is not working as well as it could be. Perhaps a mistake keeps getting repeated or a process is inefficient and cumbersome. You could call it a “problem” that needs to be fixed, but that misses another part of what you’re sensing — the potential for a solution.

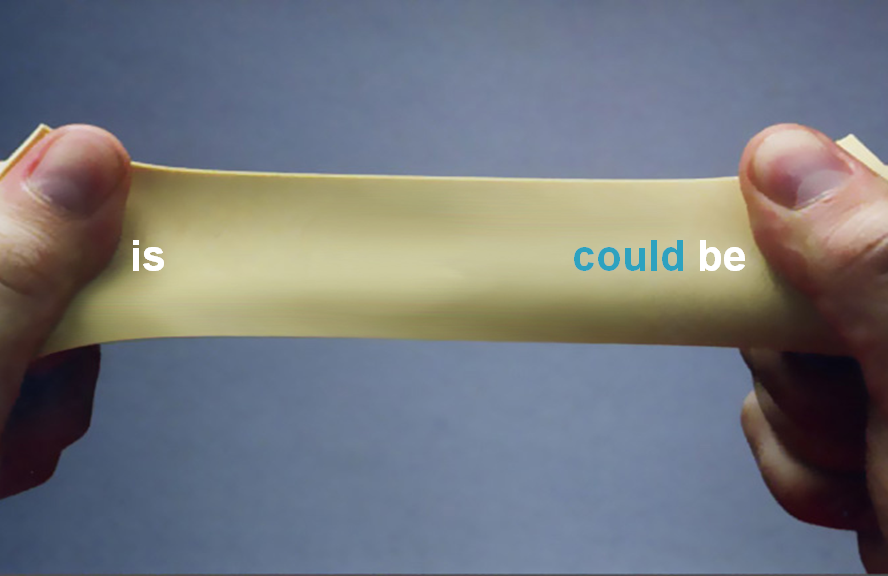

When you sense a tension, you are tuning in to a gap between how things are and how they could be.

Tensions, in this sense, are one of the organization’s greatest resources, because they reveal the pathway to growth and improvement, based on real experience, not abstract ideas.

A day-to-day Holacracy practice is all about translating tensions into meaningful change. Even if you don’t use the specific methods we use, you too can learn to love tensions and the possibilities they reveal.

2. Don’t Ask for Permission

In traditional organizations, there is often an assumption that you can’t do anything unless you’re given permission to do it. Holacracy practitioners hold the opposite assumption: you can do anything unless it’s been explicitly forbidden.

In traditional organizations, there is often an assumption that you can’t do anything unless you’re given permission to do it. Holacracy practitioners hold the opposite assumption: you can do anything unless it’s been explicitly forbidden.

Think about it — why do you feel the need to ask permission? Most likely, it’s because you’re concerned that without it, you might step on someone’s toes, and inadvertently cause problems for other people.

And while that sounds like a valid concern, it quickly adds up to a culture in which everyone feels it’s someone else’s job to prevent them from feeling tensions, and everyone blames each other for the things they don’t like. The result is fear-based inaction. This holds back both individuals and the organization.

Holacracy’s processes create trust that tensions can be resolved. We encourage individuals to take initiative and proactively respond to issues that impact their work without having to get everyone else’s buy-in. Removing the expectation that people will ask permission and the fear of causing tensions for others — unleashes far greater creativity to serve the organization’s purpose.

3. Be Selfish

Too often, in a business meeting, people try to anticipate what others may like or not like before others say what they actually want or need. We may “pre-filter” our requests and ideas so as to avoid any push-back from our colleagues.

But what if you trusted that the meeting process itself would create space for others’ objections, opinions, and concerns to be voiced, and help you decide whether you needed to take those into account? Then you could feel free to state exactly what you want or need, and other people would have that information too.

It might feel like you’re being selfish — but that can be a good thing! Imagine: If your colleagues don’t even know what you really want, how likely is it that you will find an optimum solution — one that works for you and everyone else? Holacracy facilitators encourage this in meetings by asking the person who added an agenda item, “What do you need?”

So go ahead, be selfish — let people know exactly what you think would help you serve your role better, then let them be the ones to raise the objections. You also may discover that your colleagues are in fact eager and willing to help you and are happy to be given a clear path to do so.

It’s harder for people to help you if you don’t tell them what you need.

4. Dare Not to Care

One of the most helpful things Holacracy does is create clarity around roles and accountabilities — so that you know exactly what falls within your circle of responsibility. And just as importantly, you know what does not.

As human beings, it’s in our nature to try to be helpful, and many of us have a tendency to jump in and try to solve an issue once we become aware of it. If a customer complains about something or a colleague is struggling, we want to fix it. Oftentimes, however, that’s not the best use of our time and energy. We have other priorities we should be focused on.

If a surgeon is headed into the operating room to save a life, and a colleague stops to ask her about why receptionist’s computer isn’t working, it’s critical that she does not care about that issue. Not all such choices are so clear cut, but the principle holds: By not caring about one thing, you express your care for something else.

Knowing when something falls outside your role, and saying “No, that’s not my responsibility” may feel uncomfortable, but it could be the best thing for you and for the organization. It may expose an area that needs clarifying, so that someone is explicitly accountable for that issue. If you simply absorb that tension, the organization will lose the opportunity to adapt its structure, and you’ll be distracted from the things that really need your time and attention.

So dare not to care — you’ll be helping the organization evolve.

5. Don’t Say “We”

Holacracy’s founder, Brian Robertson, likes to say, “We isn’t a good worker.” Yet too often, in business meetings, you’ll hear about all kinds of things that “we” intend or need to do. “We are ready to do something about that website.” “We need to move on that conference plan.” “We must fill that position before the end of the year.”

Holacracy’s founder, Brian Robertson, likes to say, “We isn’t a good worker.” Yet too often, in business meetings, you’ll hear about all kinds of things that “we” intend or need to do. “We are ready to do something about that website.” “We need to move on that conference plan.” “We must fill that position before the end of the year.”

When you hear “we,” ask “who?” Clarify who exactly is responsible for the action — which role will ensure it is carried through? It could be that there is no clear role to take on that accountability, but then you know that you need to define that role and assign it to someone.

If it’s everyone’s responsibility, then it will end up being no one’s responsibility.

6. Don’t Manage Deadlines with Hope/Blame

Deadlines are common currency in the business world, and most people find it hard to imagine running a business efficiently without them. We regularly promise “what-by-whens” and expect others to do the same — without them, how would we be able to count on each other for anything?

The desire for deadlines is understandable. The world has deadlines. But the old tool for managing to deadlines is to get a commitment from someone, and then hope they stick to it, and/or blame them when they miss it. The problem of course is unexpected events require us to shift priorities, and we can’t predict these when we make a commitment to a deadline.

Individuals need to be free to adapt and use their time to best serve their roles and the organization’s purpose, rather than being forced (through blame and fear) to prioritize less critical tasks simply because they made a blind promise to someone else. So instead of promising what-by-whens, try offering projections and daily updates, and then creating more transparent task management systems (we love David Allen’s Getting Things Done approach) so that everyone can see and adapt to the changing nature of reality. That’s a far better way to manage to deadlines than the old hope/blame approach.

Read more on a better way to manage to deadlines.

7. Clarify Agreements

There a common misconception that Holacracy’s processes push to make everything explicit, which in fact is not true. If something is working, we leave it alone. “It’s okay until it’s not okay” is our approach.

There a common misconception that Holacracy’s processes push to make everything explicit, which in fact is not true. If something is working, we leave it alone. “It’s okay until it’s not okay” is our approach.

When it’s not okay — meaning, when someone takes notice that something isn’t working as well as it could — often it points to a mismatch between our assumptions and the expectations of others. It’s at these moments that it’s helpful to make explicit agreements and clarify who is accountable for what.

Whether you practice Holacracy or not, it’s helpful to pay attention to where you are holding implicit assumptions about what someone is responsible for, and consider how these might be affecting your working relationships with your colleagues.

Holding an implicit agreement over someone’s head is actually a very unfair practice, and tends to lead to frustrations and disappointments. If something’s not working, check your assumptions and see if there’s an agreement you can clarify.

Learn more about Holacracy.

Contact HolacracyOne to discuss options for adopting Holacracy.

Republished with permission of the author.

Featured added by Enlivening Edge Magazine.